Note to the Reader:

This installment in the Complexity series differs in tone from earlier parts. Where previous essays moved more freely through aesthetic and metaphorical registers, this one enters more technical territory.

Metacognition, reflection, and learning theory require careful attention to frameworks and scholarship, which gives this post a denser, more academic texture. The shift is intentional and worth your time and attention: before turning to art as method, we pause here to ground ourselves in theories of how we think and learn.

***Disclaimer: Treat the term “post-think” as a mnemonic device and an interpretation of metacognition.***

1. A Held Breath After Action

At the end of every action or thought, there is a pause – a silent held breath – where meaning settles.

In this transient moment, “post-think” begins.

It is the hush after a final brushstroke on a canvas, the echo fading in a concert hall, the heartbeat in the silence following a profound question. This reflective pause is the space after cognition, a composite after-image of thought where we turn inward to make sense of what just transpired.

Educational philosopher Max van Manen beautifully describes phenomenological reflection as both sober and enchanted: a “sober reflection on the lived experience” that is at the same time “driven by fascination: being swept up in a spell of wonder”[1]. In these “indescribably swift, deep, timeless moments” of insight[1], we encounter our own understanding as if it were a held breath – suspended, attentive, and alive.

Post-think is this held breath after action, a contemplative interval where we learn by looking back. Through such reflection, the mind engages in a subtle art: the art of understanding one’s experience anew. This opening meditation frames post-think as the reflective afterglow of cognition.

Just as an artist steps back to gaze at a finished painting in quietude, or a diver floats briefly between submersion and surfacing, we too need these pauses. The complexity of experience resolves into insight only when given space. In the series on Complexity, this part explores how metacognition – thinking about our own thinking – transforms mere experience into wisdom. Reflection will be our guide through theories of mind and learning, across cultures and philosophies, toward seeing art itself as a way of knowing.

Before diving into scholarly frameworks, we acknowledge this simple truth: learning to understand requires us to stop and reflect, to hold our breath after each action, so that understanding can catch up with experience.

The poetry of post-think lies in its stillness –a quiet interlude where the mind’s eye can see more clearly.

2. Frameworks of Reflection

Metacognition, a term famously introduced by John H. Flavell, finds complementary elaboration in the work of Vygotsky and Kolb.

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle posits that learning is a cyclic process of experiencing and reflecting. According to Kolb, knowledge is created through the transformation of experience: one must do something and then reflect on that experience to learn. His four-stage learning cycle begins with a concrete experience, followed by reflective observation on that experience, then abstract conceptualization , and finally active experimentation. Notably, the second stage is where the learner “steps back to reflect” and ask questions about what happened.

It is here that raw experience is sifted for meaning.

Kolb’s model has been profoundly influential in education and professional training, underscoring that without reflection, experience alone does not yield learning. The cycle’s power lies in its systematic use of post-think: each experience must be processed in the mind, compared with prior knowledge, and consciously understood before it can guide future action. Subsequent research has confirmed Kolb’s influence, recognizing reflective learning as central to effective education. This framework situates metacognition as a necessary bridge in the learning process: it is the pivot between doing and understanding.

Together, these foundational frameworks provide a multi-faceted understanding of reflection. They suggest that post-think is at once a personal skill of self-monitoring, a dialogical process rooted in social interaction, and an experiential strategy for deep learning. The point can thus be refined: metacognition provides the cognitive basis for post-think; social constructivism provides the context in which reflective thinking develops; and experiential learning provides a cyclical model to apply reflection for growth.

With these in mind, we can delve deeper into how reflection plays out in the identity and practice of educators, the interpretation of art and experience, and the cultivation of insight through various methods.

3. The Educator’s Becoming

For teachers and educators, reflection is not just an academic exercise – it is integral to identity and professional growth.

Cherry A. McGee Banks, a scholar of multicultural education, emphasizes that becoming an effective multicultural educator requires deep critical self-reflection. In her work on teacher development, Banks argues that self-knowledge is a foundational factor: teachers must examine their own cultural narratives, biases, and assumptions as part of learning to engage diverse students[8]. One course she describes has teachers critically reflect on media, biographies, personal narratives, and professional experiences – using these as “powerful sources for deepening self-knowledge and for posing critical questions about difference and diversity”[9]. Through such reflective activities, educators begin to recognize how their background shapes their teaching and how they can transform their practice to be more inclusive[10]. Banks weaves teacher comments throughout her study, illustrating the insights gained through critical self-reflection and how this process catalyzes a teacher’s ongoing development[10].

This highlights a key point: metacognition in education often means reflecting on one’s own identity, beliefs, and biases – an inward journey that is necessary for growth in outward practice.

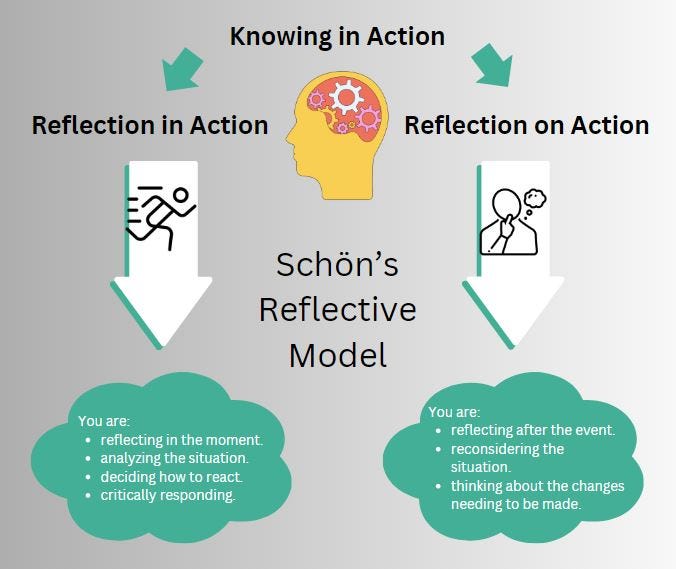

In the broader context of teacher education, the idea of the reflective practitioner has long been seen as vital to “educator’s becoming.” A teacher’s journey is not just about acquiring techniques, but about continuously reflecting on experiences in the classroom to inform future action. This notion was famously advanced by Donald Schön, who distinguished between reflection-in-action (thinking on one’s feet during teaching) and reflection-on-action (reviewing events after the fact) as modes of professional reflection.

While Schön is not explicitly part of this exploration, his influence underpins much of modern reflective practice. Educators, especially in multicultural settings, must do both: they adapt in the moment and later hold a mirror to their practice. Cherry McGee Banks’ focus on critical self-knowledge adds that teachers must also reflect on who they are in relation to their students.

Thus, the educator’s becoming is a reflective journey of identity: as Banks asserts, engaging with personal narrative and cultural context helps teachers form “contexts for multicultural engagement” by understanding themselves[8].

One refinement emerging from the literature is the importance of reflection for equity and inclusion. Metacognition in multicultural education isn’t just about thinking better; it’s about becoming better in an ethical sense – more aware, empathetic, and responsive. When Banks describes teachers posing critical questions about difference and diversity[11], she is essentially highlighting critical reflection: questioning one’s assumptions about race, culture, and power.

This aligns with broader scholarship in multicultural education (e.g. James A. Banks, Geneva Gay, and others) that calls on teachers to critically reflect on how the curriculum and their own biases affect marginalized students. In practice, tools like reflective journals, discussion blogs, and coaching conversations are used in teacher education programs to foster this metacognitive awareness.

Research indicates that teachers who exhibit higher reflective ability tend to be more effective and adaptive in diverse classrooms[12]. They are more likely to recognize when a lesson isn’t reaching some students and adjust, or to see how a student’s perspective might differ from their own. In short, post-think makes the educator. By reflecting on practice and self, teachers undergo an ongoing transformation – an identity formation process – that enables them to better serve all learners. As one study succinctly noted, students who develop greater metacognitive abilities tend to be more successful thinkers, and the same can be said for teachers[12]: a reflective teacher is a more effective teacher.

Cherry McGee Banks’ work anchors this section, showing how critical self-reflection builds the self-knowledge needed for multicultural teaching[8].

The poetic notion of “becoming” suggests an ongoing process – teachers are always on the way to being the educators they aspire to be. Reflection is the compass that keeps them on that path, allowing for course corrections and new understandings. In complexity terms, an educator’s identity is a dynamic, evolving system – one that learns and adapts through the feedback loop of metacognition. By engaging in post-think, educators cultivate the capacity to learn from their own experiences and identities, an essential step before they can guide students to do the same.

4. Hermeneutic Encounters

Reflection can also be viewed through the lens of hermeneutics, the art and science of interpretation.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, a foremost thinker in philosophical hermeneutics, offers insights into reflection as a dialogical encounter – particularly evident in how we engage with art and text. Gadamer famously argued that understanding is not a solitary absorption of facts, but a conversation: to understand something (a text, a work of art, another person) is to enter into dialogue with it.

In this view, reflection becomes a hermeneutic encounter, a form of interpretive dialogue that happens after an initial experience and deepens our understanding of that experience.

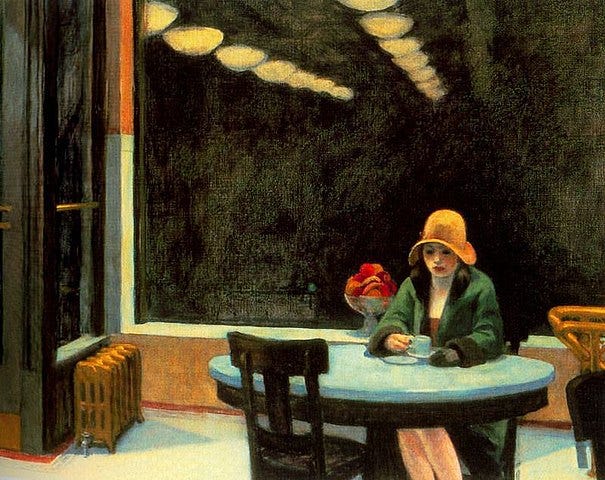

One way Gadamer illustrates this is through our experience of art.

He insists that a genuine work of art addresses us – it “says something to someone” – and in doing so, it stops us in our tracks and makes us reflect[13]. When we stand before a powerful painting or read a moving poem, we often find ourselves in a silent dialogue with it: surprised, challenged, even “dismayed” by what it communicates[13]. Gadamer notes that the experience of art is an experience of meaning, one that is “brought about by understanding”[14]. That is, art presents us with something intelligible, but we must actively engage, interpret, and integrate that meaning.

In the moment of encountering art, we undergo a hermeneutic reflection: we ask, “What is this saying? Why does it affect me? What does it mean for me?”

This reflective interrogation is not a step removed from the aesthetic experience – it is part and parcel of it. Gadamer even says “aesthetics is absorbed into hermeneutics”[15], implying that the true payoff of art is not mere pleasure but the understanding it provokes. Reflection, then, is the path by which art’s meaning unfolds to us.

Gadamer’s philosophy refines our outline by casting reflection as dialogue and interpretation rather than mere introspection. In his view, all understanding is dialogical: when we reflect, we are essentially conversing – perhaps with ourselves, perhaps with an imagined other, or with a text or artwork. He describes hermeneutical experience as fundamentally conversational, where the interpreter and the subject matter “share in bringing a subject matter to light”[16]. This dialogic nature means that reflection is not a one-sided analysis, but a meeting between horizons – our own horizon of understanding and that of the text/art/experience we are engaging.

Gadamer’s well-known concept of the fusion of horizons captures this idea: through dialogue (literal or metaphorical), our perspective merges with that of the Other, yielding new insight. In practical terms, when a teacher reflects on a challenging classroom incident, she is in a “dialogue” with that situation – trying to understand it by considering multiple viewpoints (hers, the students’, perhaps a theorist’s). When an art student reflects on their studio work, they are in dialogue with their creation – the work “speaks,” and they answer by adjusting their understanding or approach.

The use of art as interpretive encounter is especially apt.

Gadamer’s aesthetics frames art as a conversation partner that can reveal truth. He notes, for example, that a person who approaches art as mere entertainment “misunderstands himself,” because in truth we encounter ourselves in the work of art[17]. “To understand what the work of art says to us is therefore a self-encounter,” Gadamer writes[18][13]. This means that reflecting on art becomes a way of reflecting on our own being.

A painting might evoke a memory or an emotion that leads us to new self-knowledge; a drama might pose ethical questions that we must answer for ourselves. In these hermeneutic encounters, reflection is both interpretive and self-reflective – we interpret the external artwork, and in doing so, reflect on our internal world. The dialogue swings both ways.

In educational practice, adopting a hermeneutic stance could mean encouraging students to engage in dialogue with texts and artworks, treating reflection as an open-ended conversation rather than a fixed analysis. For example, a teacher might use a painting in class to invite multiple interpretations, helping students reflect on why they see it the way they do. This echoes Gadamer’s point that hermeneutical reflection is open and dialogical, resisting any single authoritative reading. It’s the questions and the act of questioning that matter. The educator’s role becomes one of facilitating this interpretive dialogue – be it through Socratic discussion, journaling about one’s response to literature, or using art as a springboard for reflection.

In sum, we’ve just shown that reflection (post-think) can be envisioned as an art form of understanding, akin to interpreting a poem or conversing with a friend. Gadamer’s perspective enriches our journey by emphasizing that to reflect is to participate in a dialogue – a dialogue that may involve artworks, texts, or our own life events – wherein meaning is co-constructed. This sets the stage for viewing art itself as a mode of inquiry, and it reminds us that even in solitary reflection we are never really alone: we are always in conversation with the voices, experiences, and artworks that have something to say to us, if we only listen and respond.

…to be continued.

References:

Banks, C. A. M. (2015). Self-knowledge as a factor in becoming a multicultural educator. Multicultural Education Review, 7(3), 155–170[8].

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911[2].

Gadamer, H.-G. (1975/1989). Truth and Method (2nd ed., J. Weinsheimer & D. Marshall, Trans.). New York: Crossroad. [Philosophical hermeneutics; art as dialogue][13][16].

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall[5].

van Manen, M. (2007). Phenomenology of Practice. Phenomenology & Practice, 1(1), 11–30[1][19].

van Manen, M. (1997). Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy (2nd ed.). London, ON: Althouse Press. [See especially on writing as reflection].

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Social origin of higher mental functions][3][4].

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and Language (A. Kozulin, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Inner speech and self-regulation].

(Additional sources in text: University of Edinburgh Reflection Toolkit[28]; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Gadamer’s Aesthetics”[14].)

(Open Access) Links:

[1] (PDF) Phenomenology of Practice

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228480543_Phenomenology_of_Practice

[2] Metacognition and Cognitive Monitoring: A New Area of Cognitive-Developmental Inquiry

[3] [4] (PDF) Metacognition and Self-Regulation in James, Piaget, and Vygotsky

[5] [6] [7] Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle: A Complete Guide - Growth Engineering

https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/kolb-experiential-learning-theory/

[8] [9] [10] [11] Self-knowledge as a factor in becoming a multicultural educator

https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_all/2051/

[13] [14] [15] [16] [17] Gadamer’s Aesthetics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/gadamer-aesthetics/

[18] Gadamer H.-G. - Dyssebeia

https://dyssebeia.wordpress.com/category/philosophy/gadamer-h-g-philosophy/