You may remember from middle school biology that mitochondria are called ‘the powerhouse of the cell’ — converting oxygen into energy.

Similarly, multimodality is the powerhouse of learning:

it translates sensory experience into cognition.

(If you enjoy geeking out over random bits of information, click here for a refresher on mitochondria, by Harvard X)

Here is where we start:

Thought arrives in color, rhythm, texture, and image.

A mind limited to language alone is a mind only half awake.

The modernist painter Wassily Kandinsky, who heard colors and saw music, exemplified this blending of sensory modes – a phenomenon known as synesthesia.

Neurologist V. S. Ramachandran notes that synesthesia is “seven times more common among artists, novelists and poets” and may underlie their “power of metaphor and the capability of blending realities”. In other words, our greatest creators intuitively mix sights, sounds, movement, and feeling into the depth of meaning. Multimodality isn’t a “learning style” or a trendy pedagogy – it’s the very essence of how human cognition fires on all cylinders.

What Is Multimodality—Really?

When we talk about multimodality, we are not just talking about using multiple media or inputs for their own sake. It’s not the old (and debunked) idea of rigid “learning styles” where each student supposedly has one preferred sense to learn with. Nor is it merely presenting the same information via slides and speech and text. Multimodality means the concurrent, overlapping, and interactive modes by which human brains make meaning. It recognizes that in real life, our understanding comes from a symphony of channels – linguistic, visual, spatial, kinesthetic, musical, etc. – all working in concert.

Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen, pioneers of social semiotics, argue that for too long Western culture favored monomodal communication (e.g. dense text in academic papers, or paintings confined to canvas). In contrast, multimodality acknowledges that “the ‘same’ meanings can often be expressed in different semiotic modes”, and that meaning itself emerges jointly from all these modes at once. Kress’s studies in classrooms show that “learning can no longer be treated as a process which depends on language centrally, or even dominantly. Our data reveals conclusively that meaning is made in all modes separately, and at the same time, … an effect of all the modes acting jointly.”

In short, we think and communicate in parallel channels – images, words, gestures, sounds – and each channel has its affordances (strengths and limits for conveying certain ideas).

The concept of modal affordances comes from Kress & van Leeuwen’s work.

Each mode offers unique possibilities: e.g. a diagram can show spatial relationships at a glance, while text can spell out abstract propositions, and music can capture emotional tones. No single mode is inherently superior; instead, they complement each other. As educator Carey Jewitt explains, meaning-making involves the “co-deployment of different modes, including language, images, gestures, and symbols”. A multimodal approach asks:

What does each mode do best?

Visuals might spatially organize concepts, while spoken words add narrative context, and touch or action provides experiential understanding. By layering modes, we get closer to how human understanding truly works.

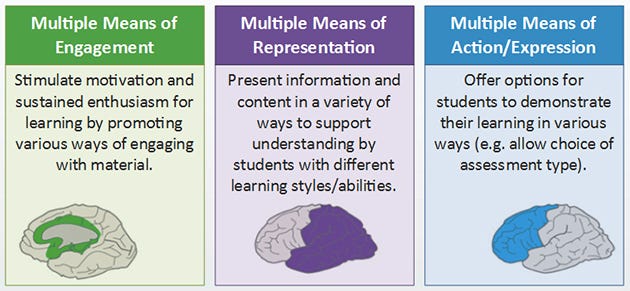

Universal Design for Learning (UDL), an educational framework born from cognitive science, also emphasizes multiple modes. UDL’s principle of Multiple Means of Representation says that information should be presented in various ways – text, audio, images, interactive media – not only to include learners with different needs, but to deepen everyone’s grasp of content. The goal is not redundancy for its own sake, but integration: Each mode reinforces and enriches the others, creating a more robust learning experience. I.e. the more modalities implicated, the better memory will be. Multimodality, at its core, is about using the full toolbox of human expression and perception to make and to make meaning.

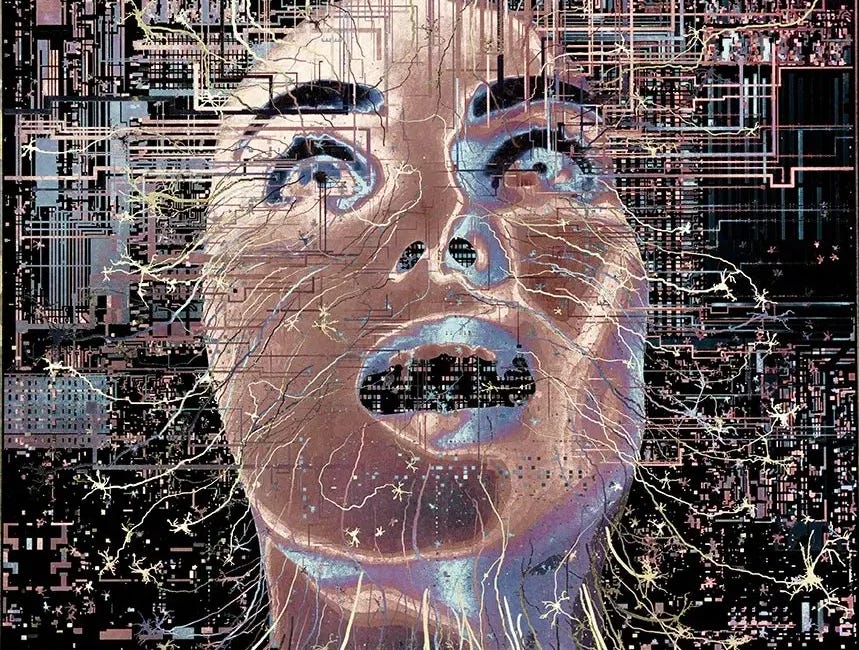

From Sensation to Cognition: The Translation Layer

How do raw sensations become ideas? Multimodality is the translation layer between sensing and understanding. There’s an old philosophical maxim:

“Nothing is in the mind that was not first in the senses.” We take in the world through sight, sound, touch, taste, and movement – but cognition begins when we start representing, organizing, and processing those sense-data in various modes internally.

Imagine a child experiencing an emotion too big for words. Say a six-year-old feels grief for the first time – a grandparent’s passing or the loss of a pet. They might not be able to verbalize it. Instead, the child draws a picture of a dark, stormy sky with rain pouring down. Later, they mold a lump of clay into a small figure curled up, and perhaps they even make up a little story about a lonely animal searching for its friend. In doing so, the child has translated the raw feeling (sensation of sadness, heaviness in the body, confusion in the mind) into visual form (the storm drawing), into tactile/three-dimensional form (the clay figure), and into narrative form (the spoken story). This is cognitive encoding across modes – each mode capturing an aspect of the experience that the others couldn’t by themselves.

Psychologist Rudolf Arnheim, in Visual Thinking, argued that perception and thinking are deeply intertwined. He wrote that “cognitive operations called thinking are not the privilege of mental processes above and beyond perception but the essential ingredients of perception itself.”

These operations – “active exploration, selection, grasping of essentials, simplification, abstraction, analysis and synthesis…” – are at work even when we simply look at something. In other words, when that child draws a storm to represent grief, the act of seeing and making the image is part of their thinking process, not just an output of it. Arnheim concluded, “visual perception is not a passive recording of stimulus material but an active concern of the mind.”

The child organizes their inner turmoil by giving it shape and color – a direct example of sensation evolving into cognition through multimodal representation. Cognitive science offers further insight into this translation layer through theories of multimedia learning.

According to Allan Paivio’s Dual Coding Theory, our minds have two major channels for encoding information: a verbal (linguistic) channel and a nonverbal (often visual) channel. Information encoded in both modes (words and images) has dual “codes” in memory, creating extra associations. For example, if you hear the word “dog” and also see a picture of a dog, you store it in two forms – later you might recall the image to retrieve the word or vice versa. The imagery acts as a second hook for memory, increasing the chances of recall. Likewise, our six-year-old may not remember a spoken explanation of “grief,” but they will never forget the drawing they made – the concept has been grounded in a concrete visual metaphor, making it stickier in memory.

Educational psychologist Richard Mayer extends this idea with his Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, which includes principles like the Multimedia Principle (people learn better from words and pictures together than from words alone) and the Modality Principle (people learn better from visuals + spoken narration than visuals + printed text).

One important caution is the Redundancy Principle: more modes are not always better if they are truly redundant. For example, narrating an animation while also displaying identical text can overload the learner’s cognitive capacity. The key is to ensure each mode contributes something unique – a concept called complementary redundancy rather than verbatim duplication.

In the “grief storm” example, the child’s picture expresses an atmosphere (dark clouds, rain) that words alone might not convey; if an adult then talks gently with the child about the picture (“It looks like a very sad storm”), the verbal mode validates and extends the visual mode. Through such multimodal encoding, sensation finds symbolic form, and the child can begin to think about their feeling. Multimodality is thus the transmutation that converts the lead of raw experience into the gold of understanding.

A student illustrates a concept through drawing. Converting ideas into images engages multiple cognitive pathways, strengthening memory. Research shows that drawing is an “active process” – the tactile movement of pencil on paper plus the visual feedback “strengthens the cognitive pathways” that lead to durable understanding.

Even in adults, we rely on cross-modal translation to comprehend complex ideas. Think of a time you doodled a quick sketch to explain a problem, or moved your hands while searching for the right words. That’s your brain switching modes to leverage different strengths. Our minds don’t limit themselves to one modality when grappling with tough questions – why should our teaching and learning?

Multimodal Learning Design in Education

What does all this mean in the classroom or the workplace?

Multimodal learning design takes those principles of concurrent meaning-making and puts them into practice. In essence, it means crafting learning experiences that invite learners to engage with content in multiple modes – and to express their understanding in multiple modes. The evidence is overwhelming that this leads to deeper learning.

The Edutopia feature “The Power of Multimodal Learning (in 5 Charts)” presents a large body of research on this. One highlighted study found that 8-year-olds learning vocabulary in a new language had 73% better recall when they acted out the words with gestures and body movement, compared to just memorizing definitions. Another meta-analysis of 183 studies concluded that pairing words with meaningful actions (like having students physically model the orbit of planets while learning astronomy) was a “reliable and effective mnemonic tool”. In short, doing while learning – drawing, moving, speaking, singing – encodes knowledge more powerfully than listening or reading alone.

So how can we design learning that is richly multimodal?

One way is to present material in diverse forms and then have students represent it in diverse forms. For example, consider a science lesson on the water cycle. A teacher might introduce the concept with a story or narrative (describing a day in the life of a water droplet), show an infographic diagram of the cycle, and perhaps play a short animation of evaporation and rain. The students then might engage in a role-play activity acting out the parts of the cycle (one student evaporates “up” as the sun, another condenses into a cloud, etc.). They could follow this by creating something like an artistic poster or a comic strip that illustrates the water cycle in their own way.

Each modality here reinforces the concept: the narrative gives it temporal logic, the diagram gives it structure, the role-play gives it physical experience, and the art project gives it personal creative investment. This isn’t just throwing everything at students; it’s constructing a multilayered understanding. As one cognitive scientist put it, “the more naturalistic, multi-sensory context provides a wealth of information” for the brain to latch onto.

Dual Coding Theory comes into play in such designs – students are encoding the water cycle verbally, visually, and kinesthetically, forming multiple mental connections. In a 2020 study, one group of students was taught fractions with traditional lectures and worksheets, while another group learned through a hands-on embodied activity: they played a modified basketball game where sections of the court were labeled with fraction values, and scoring involved moving on a giant number line. The result? The physically active kids saw 8% to 30% improvements in fraction skills, far outpacing the 1% improvement of their desk-bound peers. The game was “playful, engaging, embodied, ... rooted in cognitive science research”, showing how a cleverly designed multimodal lesson can yield serious academic gains.

However, a caution from Mayer’s research: while designing multimodal content, avoid pure redundancy that can cause overload. For instance, if you have a video with spoken narration, you don’t need a text paragraph on screen repeating the exact same words – that can split the learner’s attention or overwhelm the language channel. Instead, combine complementary modes: graphics + brief labels, or narration + animation, etc.

Use the Redundancy Principle to guide you: people learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics, narration, and on-screen text (doing all three can be extraneous). In practice, this means in our water cycle example the teacher wouldn’t simply read aloud text that’s already on the infographic; they would either let the graphic speak visually while narrating context, or let students interact and describe it in their own words. One effective strategy is allowing artistic representation as output.

In Part 2 of this series, we discussed embodied learning as a powerful input (experiencing through the body). Multimodal thinking is the integration stage – the mind weaving inputs into its networks. Now, when learners create an artistic or expressive output, they are effectively teaching the concept back to themselves in a new mode, which demonstrates true mastery.

A student might write a song about a historical event, or build a physical model of a molecule, or choreograph a dance showing a math concept like symmetry. These are not just “extra credit art projects” – they are core to learning.

As psychologist Jerome Bruner famously said, “You know you understand something when you can translate it into a different form.”

When teachers encourage students to show their knowledge through varied media, they tap into what the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework calls Multiple Means of Expression (giving students different ways to demonstrate understanding). One student might shine in a speech, another in a comic strip, another in a sketchnote or concept map. Multimodal design in education is about leveraging all these pathways to deepen learning and include everyone.

Art as the Perfect Multimodal Vessel

If multimodality is the engine of meaning-making, then art is its ultimate vessel. The arts have always been multimodal by nature – a sort of cognitive compression algorithm that packs ideas, emotions, and sensory experiences into dense, metaphor-rich forms.

Consider a painting: it’s visual art, but it communicates a narrative, evokes visceral emotional responses (through composition and forms), and even suggests sound and motion (think Edvard Munch’s The Scream) all in one static image. A piece of music might likewise conjure images in the mind’s eye or stir up tactile memories. A well-crafted poem isn’t just language; it has rhythm (auditory mode), imagery (visual mode), even a spatial layout on the page that affects how we read it. Artworks often layer modes simultaneously – this is sometimes called semiotic layering in multiliteracies theory.

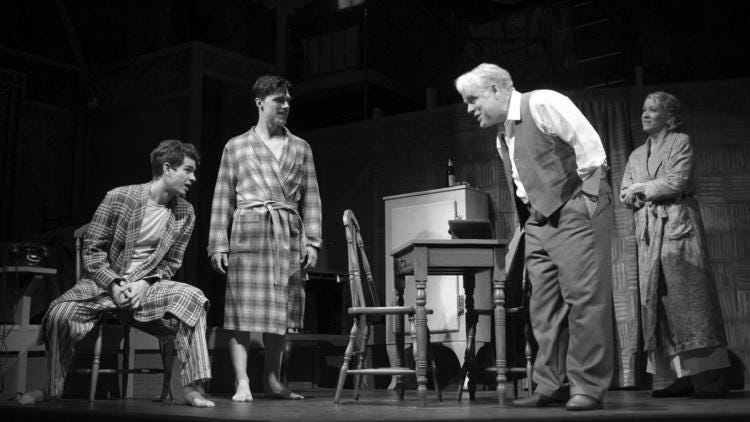

Take theater as an example: it blends spoken language, written narrative, gestural acting, set design (visual-spatial), lighting and music (aural), sometimes dance (kinesthetic). The meaning emerges from the combination.

Or take a more everyday artistic practice: graphic novels.

They seamlessly integrate text and imagery; the reader’s understanding comes from reading the words and interpreting the pictures and their interplay (panels, spatial layout, symbols). This concurrent processing across modes engages more of the reader’s brain, often leading to deeper immersion. Art, in essence, exploits multimodality to encode information densely. A single symbol in a painting (say, a red rose) can carry layers of meaning (love, blood, anger) that would take paragraphs to explain in prose.

This is cognitive compression – maximizing meaning per ounce of medium.

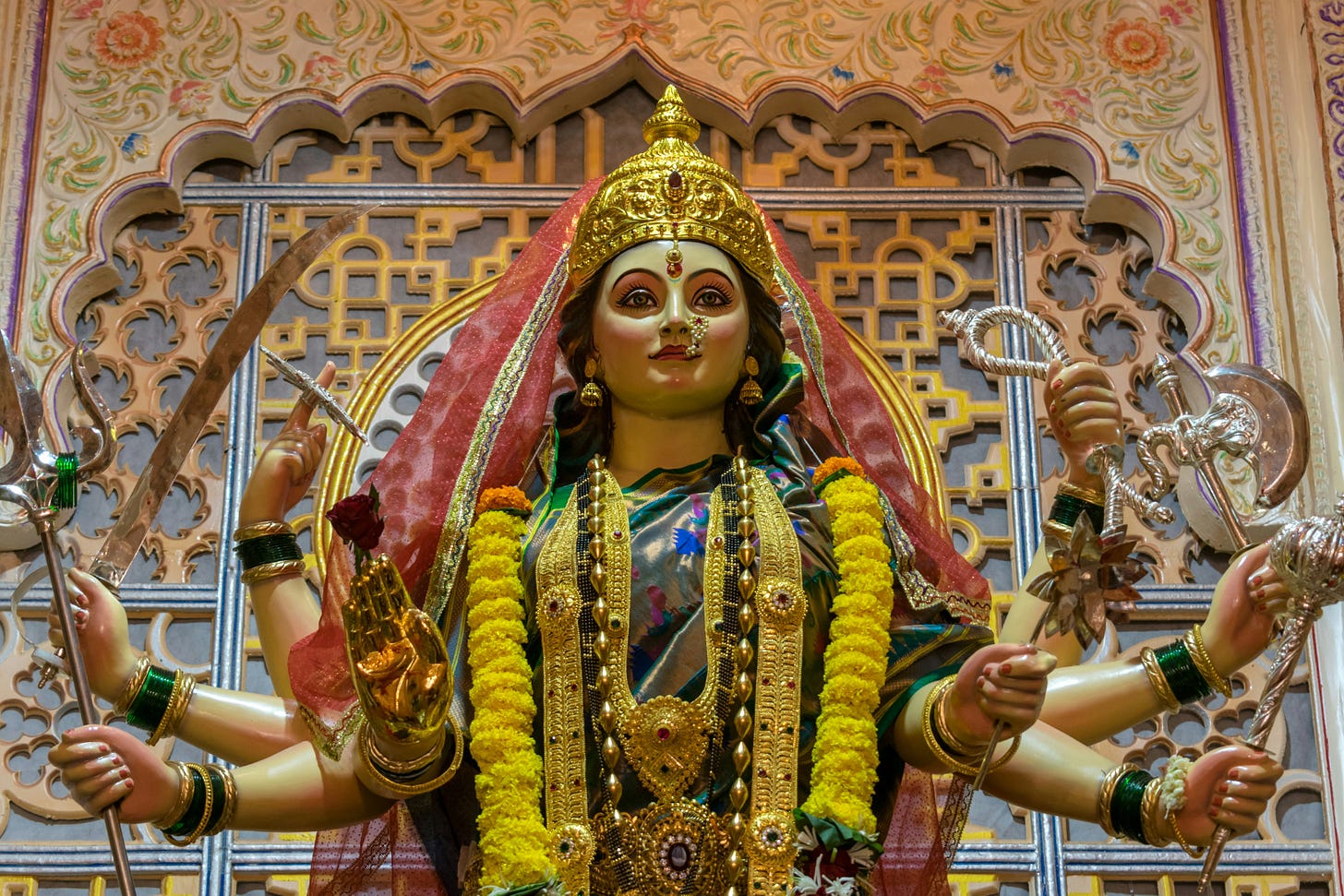

And this is not at all new. Ancient Hindu temples marry architecture, sculpture, light and sound to create an immersive spiritual experience.

A Hindu temple “carefully utilizes the power of sound and light to heighten and elevate the experience of worshipping a deity”. Every column and chamber is positioned not only for visual grandeur but to act as an acoustic device – chants and bells echo and reverberate in specific ways by design. Think of walking into a grand cathedral or temple. Your eye is drawn upward by towering columns and glittering icons (visual mode engaging spiritual awe), your ears catch the echo of a choir or a priest’s chant (auditory mode inducing reverence), you might even feel the cool stone and smell incense (tactile and olfactory cues).

The total experience is multimodal, orchestrated to move the soul.

In Hindu temple design, as the example above illustrates, nothing is accidental – architects for centuries refined designs to shape soundscapes inside holy sites. Intricate carvings and domed ceilings were not just aesthetic; they diffused and reflected sound, turning the temple into a resonating chamber for mantras. The result is that devotees don’t just hear their prayers – they feel them humming in their chest as the sound waves bounce through the stone halls. This is art as cognitive architecture: encoding cultural and spiritual knowledge in multisensory form. The worshipper’s understanding of the divine is enhanced by this blending of sight, sound, space and ritual action. This example underscores how art transcends “expression” and becomes a form of knowing.

Psychologist Howard Gardner noted that the arts are “languages” of thought in their own right – a way the mind thinks through material that is not reducible to words. A sculptor, for instance, is thinking in 3D forms and textures; a musician is thinking in patterns of sound and time. These modes allow ideas to be worked out and communicated in ways linear text cannot.

The term cognitive compression fits well here: a symphony can communicate an entire emotional journey of conflict and resolution in 30 minutes of organized sound – compressing experiences and insights without a single word. Similarly, a political cartoon can crystallize a complex social critique into one image with a few words, leveraging cultural symbols and visual metaphors.

It’s not magic; it’s multimodality.

Leonard Bernstein, the iconic composer and conductor, believed that education should echo the qualities of a great symphony: layered, dynamic, participatory, and artful. His Artful Learning model captures the spirit of multimodality in action, offering an educational framework that integrates intellect, imagination, and artistry.

At its heart, Artful Learning invites students to encounter a big idea — a concept or theme — not as a dry abstraction, but as a lived experience. The model unfolds in four movements:

Experience: learners are immersed in a sensory-rich, often artistic encounter that sparks curiosity.

Inquiry: they generate questions and investigate the big idea through multiple lenses and disciplines.

Creation: they express their understanding by producing something — a performance, a piece of writing, a work of art — using whichever modes resonate most.

Reflection: they look back on what they’ve made and learned, deepening comprehension by articulating connections.

This approach exemplifies how multimodality empowers learners to translate and integrate meaning across modes — from sensation to thought to creation. Bernstein himself called it “the artful process of learning through art”. In this vision, learning becomes not just acquisition, but composition — a weaving of modes into a personal and collective understanding.

Art is also the ideal proving ground for expressive freedom.

In an inclusive classroom, students might choose an art form to express understanding because it aligns with their strengths or interests. One student might pick painting to show their interpretation of a literary theme, another might pick a short film. By honoring these modes, we don’t just get prettier presentations – we get more authentic cognition from each learner. The student is able to use their best mode to encode their understanding, often surpassing what a written test could reveal.

Moreover, when others experience that student’s art, they might grasp the concept in a new light too – art communicates on many wavelengths at once. In summary, art is multimodality at full throttle: visuals, textures, symbols, narratives, emotions all coalescing. It compresses and communicates human experience in ways that engage multiple senses and sense-making processes simultaneously.

When we fold art into education (and life) as a fundamental mode of thought, we tap into this powerhouse of cognition. We also loop back to where we started: those who can think metaphorically, synesthetically, across domains – like Kandinsky hearing color – are leveraging multimodal thought for innovation. Small wonder that encouraging artistic, multimodal thinking in “non-art” fields (science, math, civics) has been shown to spur creativity and deeper insight.

The modes may be different, but the mind’s engine is the same: combining modalities to enrich meaning.

Policy and Ethical Implications

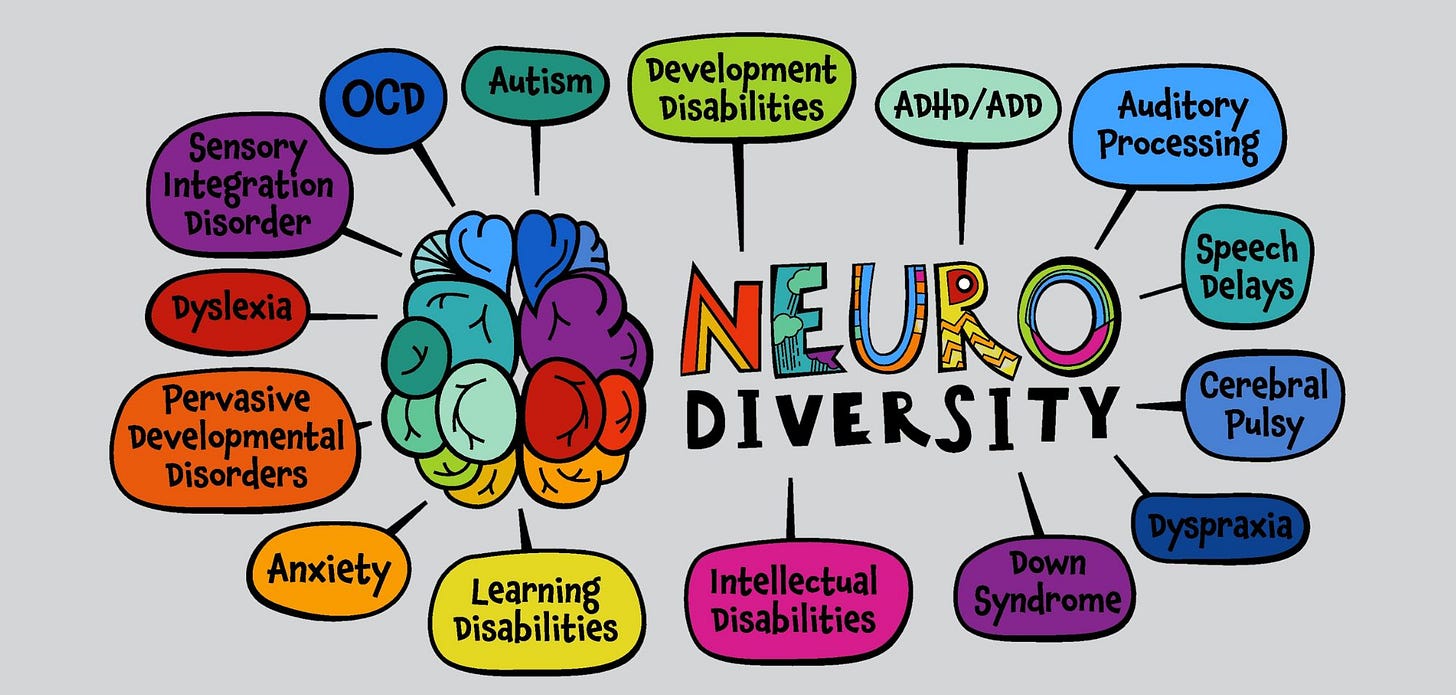

All this carries a profound message about equity and inclusion in our learning environments. Who gets left behind when schooling or workplaces insist on monomodal communication (usually text-centric, analytical, one-size-fits-all)?

Often, it’s those whose strengths or ways of knowing don’t fit the narrow mold. Neurodivergent (ND) learners, for example, may have brilliant minds that work in pictures or patterns rather than in linear language. Research shows that autistic learners often excel when allowed to express knowledge through visual, spatial, and tactile means alongside language — a strength rooted in their heightened sensory and pattern recognition abilities (Baron-Cohen, 2017; Mottron, 2011). For example professor and innovator Temple Grandin (who is also autistic) famously said, “I'm a visual thinker, not a language-based thinker. My mind works like Google Images.”

In traditional school, a mind like Grandin’s – full of rich imagery and spatial reasoning – might struggle with endless written reports but excel when allowed to sketch, build, or diagram. If we only validate one mode of “intelligence” (typically verbal/linguistic or mathematical-logical), we are not only excluding many learners; we are denying the whole group the benefit of diverse thinking styles. Grandin herself had immense contributions in animal science precisely because she could visualize problems that others only approached verbally.

English Language Learners (ELLs) are another group who suffer under monomodal approaches. A student still acquiring English might be a whiz at understanding concepts if they’re shown visually or acted out, yet standardized tests or text-heavy lessons might wrongly mark them as “behind.”

Research in second-language acquisition shows that multimodal cues – gestures, facial expressions, diagrams – significantly aid comprehension.

One recent Scientific Reports study found that meaningful hand gestures and lip movements reduced the processing difficulty (measured by brain response) for L2 learners listening to speech, leading to easier understanding.

In plain terms, an English learner benefits enormously when a teacher uses expressive intonation, points to objects or images, and uses the body to convey meaning alongside words.

Monomodal (speech-only) teaching literally leaves these students in the dark.

By contrast, a multimodal approach not only helps ELLs catch up faster, it builds a classroom culture where everyone picks up multiple ways to communicate – a good life skill in our diverse world.

Students who have experienced trauma might also engage better with alternative modes. Trauma can shut down the brain’s verbal processing centers (hence why talk therapy can be difficult at first for trauma survivors). But modalities like art, music, or movement can provide safer outlets to process and express experiences without re-triggering verbal narratives of the trauma. In a trauma-informed, multimodal classroom, a student upset by something may choose to free-write in a journal (linguistic mode for private processing) or draw their feelings (visual mode) or use stress-relief physical objects (tactile mode) – different paths to self-regulation and expression.

A monomodal classroom that demands “use your words!” for everything might inadvertently silence those students. Multimodality, on the other hand, is inherently human-centered: it recognizes that we have many ways of knowing and expressing, and it invites the whole person into the learning space.

There’s also a cultural and political dimension.

Standardized education historically elevated certain modes (e.g. written essay) as “higher” forms of knowledge, while devaluing others (storytelling, visual arts, hands-on craft) as mere hobbies or folk traditions. This often carried colonialist assumptions – indigenous and global-majority people knowledge systems that encoded knowledge in oral narratives, dance, or ritual were dismissed as primitive. Re-embracing multimodality is an act of intellectual pluralism. It says that a Navajo sandpainting or an Akan drum proverb carries wisdom just as real as a philosophy treatise – and often, conveys it in a more holistic way.

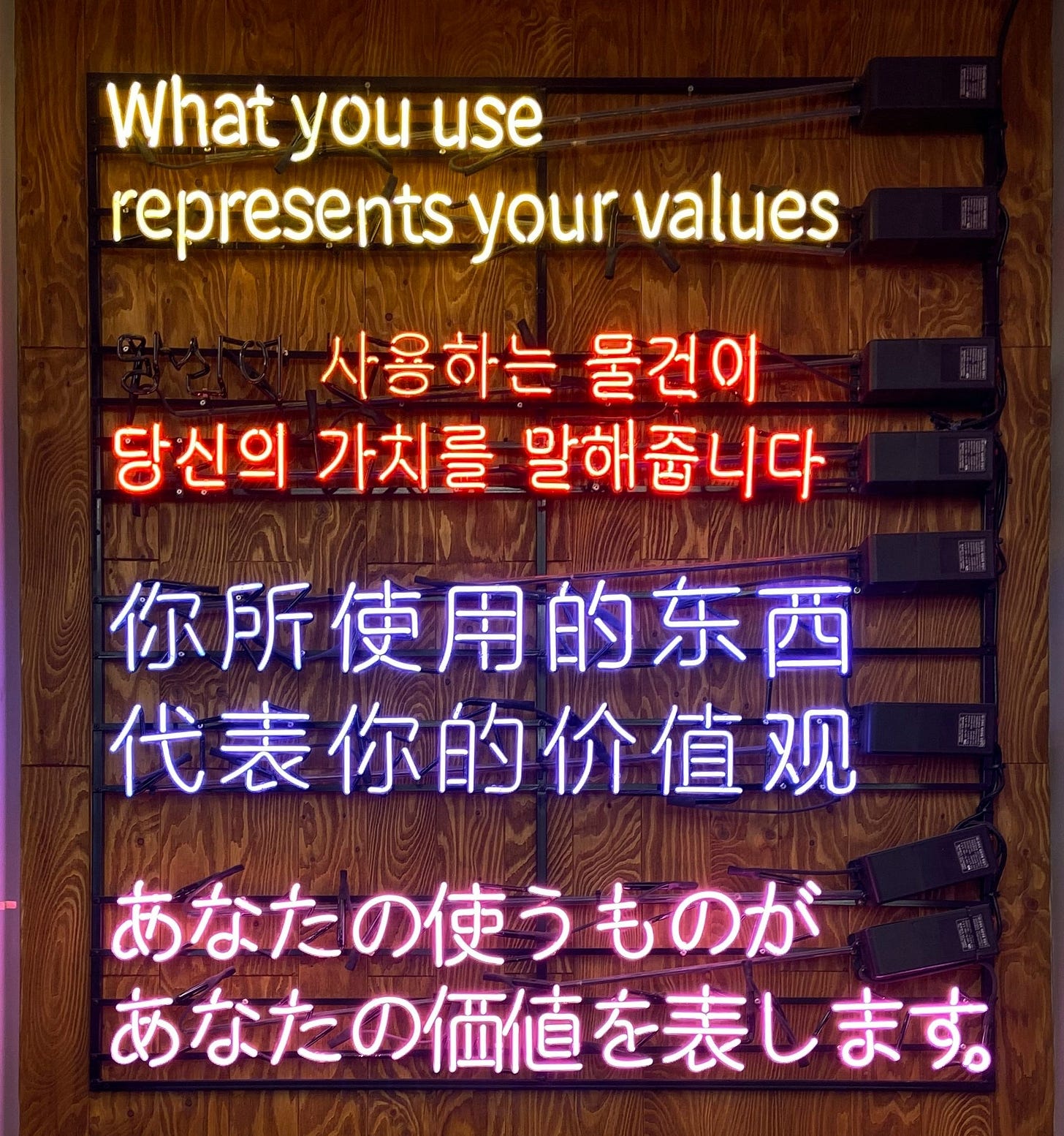

In today’s information age, we actually see a return of multimodality: think of how ideas spread on social media through image memes, videos, and infographics as much as through text.

The academy might still privilege text, but the public engages with richly multimodal content. From an ethical standpoint, insisting on one mode is a form of gatekeeping. It preferences those whose brains or backgrounds align with that mode and marginalizes the rest. Conversely, multimodal pedagogy is inclusive by design – and, crucially, it’s not just “dumbing down” for inclusion; it’s intellectually superior for everyone.

Studies show that all students learn more durably when taught with multi-sensory methods. And creative, multimodal assignments often push high-achieving students to new levels of insight because they can’t just rely on rote verbal fluency; they have to translate and synthesize understanding in new forms.

Everyone benefits.

As one educator put it, “Inclusion benefits ALL students, not just those with labeled needs.” When we embrace multimodality, we move away from a deficit view (i.e. “Johnny can’t write well, so let’s allow him to draw a comic instead”) to a strengths-based view (“Johnny has a vivid visual imagination; if he draws a comic of the story, it might actually contain insights the essays missed”).

We should also acknowledge how this connects to identity and authenticity.

A multimodal approach values the whole person – their culture (maybe they communicate in storytelling or song), their personality (a dramatic kid can shine doing a skit, a shy kid might prefer writing a poem). It lets students “take off the mask,” to borrow from Paul Laurence Dunbar’s famous metaphor, and bring their true selves into learning.

As one teacher wrote, what if curricula became a space of healing and empowerment through multimodal instruction, especially for students who feel they must hide parts of themselves?

By allowing multiple modes, we allow multiple identities to coexist and flourish.

A student can be a mathematician and an artist, an engineer and a storyteller. No one facet has to be suppressed. In a sense, multimodality in education is a step toward educational justice – it honors the many “ways of knowing” that human beings have developed, rather than enforcing a narrow pathway that historically only a privileged subset could easily navigate. Sir Ken Robinson, in his famous TED Talk Do Schools Kill Creativity?, humorously observed:

“We start to educate children progressively from the waist up, then we focus on their heads, and slightly to one side.”

By this he meant that schools often prioritize the brain (and specifically the left-brain language/logical functions) at the expense of the body, senses, and creative impulses.

The political implication of multimodality is a direct challenge to that paradigm. It asserts that we will not squander the diverse talents of students by forcing them all into one mode. Instead, we will cultivate an environment where using multiple modes is the norm, not the exception.

This is not just “nice to have” – in the complex world of the 21st century, the ability to understand and communicate in multimodal ways is critical.

Visual literacy, media literacy, the ability to read a room’s mood (social/gestural literacy), the ability to convey a message in story or infographic form – these are skills as vital as traditional print literacy. Those fluent in multimodal thinking are likely to be more adaptable, creative, and empathetic thinkers.

Closing Reflections

If you were the child who sketched in the margins but was told to stick to essays, what might have unfolded if that drawing had been welcomed as a way of learning history or science?

If you expressed yourself more fully through speech than text, what could you have discovered if school invited you to record stories or debates instead of only writing papers?

We cannot rewrite our past, but we can shape the future for those who come next. That begins with honoring the multimodal richness of thought — already alive in every learner — and giving it room to grow.

Multimodality reminds us: learning is not a single road. We’ve seen how experiences become representations, how translating between modes deepens understanding. And translation is not a straight line. A sketch or model sparks a new idea; a gesture feeds back into thought. It is a living, improvisational cycle — like a jazz ensemble, each mode riffing, responding, and building on the others.

Coming Up: Doing as Thinking

In Part 4, we step into the workshop and studio — the places where thought and action merge. Doing is not just the execution of an idea but its evolution. As artists, engineers, and students show us, making something transforms understanding; each mistake, each iteration, becomes fuel for insight.

This is the natural next step in multimodality: embracing not only multiple ways of representing ideas but multiple cycles of expressing and refining them. A concept may move from mind to sketch to prototype to performance, changing and sharpening at each turn.

Now we enter the spaces where translation becomes transformation — where ideas are embodied, tested, and reimagined through making. In Part 4, we explore how doing completes the loop of learning, turning theory into practice and imagination into innovation.

Join us there — tools ready, imagination awake.

If you are just joining the COMPLEXITY series: